Cumhuriyet Book Supplement Editor Turhan Günay: Stick in there – we’ve reached the end

A joke-like date. 24 July is the day celebrated as Press Holiday to mark the lifting of press censorship. But what ensued was not a holiday. Following a five-day hearing, seven of our colleagues were released.

Erdem Gül

Five of our colleagues are still there. We are awaiting the 11 September hearings. With us waiting for this event, the seven colleagues who got out spoke to their paper about their nine-months’ incarceration and subsequent feelings and thoughts.

Cumhuriyet is Turkey’s oldest newspaper. So, it is no stranger to courting trouble. The most recent operation against Cumhuriyet was conducted on 31 October 2016. Cumhuriyet’s foundation members, editor-in-chief and columnists were arrested in a morning raid staged on their homes.

Following five days in arrest, Murat Sabuncu, Kadri Gürsel, Turhan Günay, Musa Kart, Güray Öz, Hakan Kara, Bülent Utku, Mustafa Kemal Güngör and Önder Çelik were detained. Akın Atalay was abroad at the time of the operation. He came from Germany under his own steam. But, “flight risk” was one of the grounds for Akın Atalay’s detention, too. Then, their number was swollen by the prisoner of all seasons, Ahmet Şık. And Emre İper after him. They were charged with affiliation to as many organisations as there are in Turkey. They were placed in Silivri Prison, which has come to symbolise the political trials of recent times. But the Silivri they entered is no longer the old Silivri. Turkey was being governed under a state of emergency. And it was prisons above all that came under the state of emergency.

The comment that above all sticks in my mind by those who witnessed incarceration in the 12 September period was that prisons are “the regime’s mirror.” While they were in Silivri, what the mirror projected to us was that writing and receiving letters was forbidden, books were forbidden, visits by lawyers were one hour a week, it was forbidden to see anybody else apart from the three people sharing a cell, and it was permitted to walk and run in the cell but forbidden to go to the sports hall. I also spent 92 days in detention along with Can Dündar in the same prison on account of a news report of mine that made the headlines in Cumhuriyet. But it was not quite the same. We were detained on 26 November 2016. That is, there was a difference of about one year. But, Silivri has turned into a different prison in one year. We complained about negative aspects of our detention, principally solitary confinement. But, comparing this to what our colleagues went through in the same jail, I can’t help but say, “We stayed in a Tulip Age prison.” Our colleagues were first able to appear before a court on 24 July following a full nine months in detention.

A joke-like date. 24 July is the day celebrated as Press Holiday to mark the lifting of press censorship. But what ensued was not a holiday. Following a five-day hearing, seven of our colleagues were released. Five of our colleagues are still there. We are awaiting the 11 September hearings. With us waiting for this event, the seven colleagues who got out spoke to their paper about their nine-months’ incarceration and subsequent feelings and thoughts.

I held the Justice March in the cell

There is harsh solitary confinement in Silivri. You cannot see your colleagues. Should you encounter one another in the corridors, you cannot even inquire, “How are you?” You try to signify the sending of a greeting with a nod of the head.

I have never encountered such a nonsensical, such an unfounded indictment. You are held inside for nine months on evidence that is not evidence. It is both a comical situation, and a tragic one for those who drafted the indictment.

The most important event over the nine months spent inside was CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s justice march. I took part in the march with the word ‘Justice’ inscribed on a piece of paper from a file attached to my chest.

- You said at the hearing that 786 lawsuits had previously been brought against you, but you had not seen such a bad-faith one as this 787th lawsuit.

TURHAN GÜNAY: I started out in journalism in 1968. The number that you have also mentioned is the total number of lawsuits brought against the nearly twenty or so magazines for which I was initially a freelance reporter and, having been taken on full-time, editor-in-chief. The great majority of these lawsuits came about while I was serving on two renowned humorous magazines. These lawsuits were brought in the abnormal times of the 1971 and 1980 coups. The grounds for almost all of these were nonsensical, but we were living through abnormal times and there was a logic to the grounds cited. But, when you defended yourself, the grounds that you put forward were accepted and you were released following arrest. I think in more than twenty of them I was released following the arrest order. In short, I was never detained. As to the arrest that led to my nine months’ detention, it was a travesty. Even though I explained many times to the prosecutor who took my statement while under arrest that I had no connection with the charge raised against me, I was still detained. In the periods I spoke of, the press courted a respect that was influential among administrators. I think it was this respect that prevented me from being detained.

We did not become consumed with pessimism

- Everyone was united in thinking, ‘Old Turhan will get out first.” Was this what you sensed, too?

While under arrest, the basic thought of all my colleagues and our lawyers was, “They’ll let you go, mate.” This kept on cropping up in conversation. For my part, I thought, “If they let anyone go, they will either let us all go or detain us all,” and I vented this thought, too. I kept on thinking that there would be a righting of the error and we would all walk free together. In short, none of my colleagues, myself included, became consumed with pessimism. We stood tall, because we knew that we were in the right and innocent.

You could not even imagine it

- You had never been detained before, but you had an idea about prison, for sure. What was your impression of prison compared to before?

The information I acquired from personal experience and from visits to my colleagues who were imprisoned in 71 and the 80’s makes it clear that what was happening was not a period like today. In Silivri, conversely, there is harsh solitary confinement. You cannot see your colleagues. Should you encounter one another in the corridors, you cannot even inquire, “How are you?” You try to signify the sending of a greeting with a nod of the head. While I could easily visit my colleagues who were detained at 12 March and 12 September and take in books, such a thing defies imagination in Silivri. We were unable even to get hold of books in the first months, because the books in the institution library were extremely limited and were aimed at a restricted audience in terms of content. The Publishers Association and our publishing houses immediately intervened in this situation and created a very expansive library in a short time. In the first days on which we went inside, they handed us a library list. There were 1742 books on this list, while on the day on which we were released there were more than ten thousand books in the library. Also, at the end of the first month, the opportunity was granted of getting books from outside with our own money through a unit named the “External Canteen”.

We have seen books thanks to you

As I was frequently taken for checks at hospital and by doctors, the most frequent comment I heard from detainees I travelled together with was, “Thanks to you lot we have cast our eyes on books. We thank you immensely.”

- There are photographs of detainees in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer periods. But they denied us permission for this. Were you able to take photographs?

Take photographs? You cannot even dream of it. Not only do detainees and convicts have devices of all kinds confiscated, it is also impossible for visitors to come on visits with telephones or other devices. They just took our photos for the institution identity card the institution issues you with.

Sense of incarceration

- Experienced lawyers say that the sense of incarceration starts after one or one and a half months. That’s how it was with us. How were things with you?

This may be how it is in theory, but, if you want the truth, I never felt myself to be incarcerated. As soon as I got inside, I became engulfed in the halo of love emitted by my children Ahmet and Elif, my siblings and relatives, Turkey’s writers and publishers and the world’s writers and publishers. As to me, I had long since succumbed to the healing embrace of literature. So, I can say that I experienced no sense of incarceration.

- Did you find yourself engulfed in pessimism thinking, “We will not be able to get out any more. They will not let us go?”

No, I did not.

A tragic indictment for those who drafted it

- The wish is to put journalism on trial and deem it a crime. Your case is the most typical in this respect. You also put this across at the trial.

Our indictment contains, as you have also mentioned, simply opinion pieces, newspaper reports and nonsensical witness testimony, rather than evidence on which an indictment should be based. I have encountered some most ridiculous charges and indictments over my journalistic life, but I can comfortably say that I have not encountered such a nonsensical and such an unfounded indictment. I have also looked at the evidence on which the indictment is based and that purports to be evidence and amounts to thirty binders. In drafting or putting together a judicial text, your statements and allegations must initially rest on a sound logical basis and sound evidence. However, there is nothing tangible either in the indictment or the binders. And you are held in detention for nine months on such an indictment and evidence that is not evidence. It is both a comical situation, and a tragic one for those who drafted the indictment.

- What do you say about the meaning and importance of newspapers and, of course, Cumhuriyet for the detained journalists?

A journalist’s basic worry is the worry over missing events experienced in the course of the day. So, you look with great care and concentration at all the papers you get hold of in the morning. This is more or less ingrained in your genes. Hence, when the papers came in the morning – and the papers came at 10 am during the week and at 12-12.30 at weekends – we would start our reading with the first paper we got hold of. Then the papers would pass from hand to hand. Apart from being an employee, Cumhuriyet has a special place for every journalist. This is undoubtedly what we looked out for first. You are definitely consumed with curiosity as to what the paper will be like when it gets to you. Actually, I was not greatly disappointed. In places, we took exception to articles over their wording, but Cumhuriyet is always Cumhuriyet. The detaining of important columnists and managers can certainly undermine a publishing organ. So, we attributed such lapses to our colleagues’ tiredness in the face of their exceptional efforts.

- Over your nine months’ detention, what was the most important political and social event on the outside for you?

The most important external event over the nine-month period was undoubtedly virtually the whole world standing alongside Cumhuriyet. The most important domestic event was also undoubtedly the justice march staged by Mr Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. In the final analysis, we knew that we were not alone, but these two events brought this home to us in concrete terms. I also took part in the justice march. For sure, you needed to be on the outside to participate in such a march, but on the inside on the first day of the march I took part in the march with the word ‘Justice’ inscribed on a piece of paper from a file attached to my chest. Of course, they cannot detain your imagination and heart. The Justice March was a long march for me, too.

I swore most when I was together with Güray Öz.

For sure I did. Maybe I saw swearing as being a way of reacting. I suppose I swore most when I was together with Güray Öz. A refined man of the world like Güray most certainly does not swear and is staunchly opposed to swearing. I just did it to wind him up and hear the retort from him each time, “I will delete these from your dictionary.” I apologise profusely to Güray. But I will not delete these swearwords from my dictionary, because I know them to be a linguistic enrichment. I would like to respectfully remember Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu here. He said in a poem, “At the very least, you will speak three languages/At the very least, you will charge cussingly through three languages.” I can’t say for sure if swearing has an importance in jail, but given that people do this, I reckon that it has an importance for those who do it.

I shaved my beard after my friends asked me to

- I heard that you grew a beard.

I thought of growing a beard as a protest action. I have never grown a beard, after all. I planned to continue this action until getting out. After I had sprouted quite a beard, my cellmates Kadri Gürsel and Musa Kart began to object to my bearded state. They started commenting that they had forgotten my face and the person lying in the bed next to them was not their mate Turhan. I conceded the point to my friends and got the institutional barber to shave off my beard. Prisoners in classical literature and cinema are almost always bearded. Maybe they were bearded because the means available at their time impeded them from shaving. It must not be forgotten that one of the most important prisoners in the history of literature, Dostoyevsky, did not shave his beard for the years of his incarceration.

Staying inside and resisting is a form of activism

- Can you remember the event that caused you the most anger?

I am not one to get angry easily. You get angry and worked up about some things, for sure. But, then you soon forget about them. So, I cannot remember an event that I got very angry about.

- Which were the best moments in jail?

The chats I had with Musa Kart and Kadri Gürsel most certainly constituted the best hours in jail. In addition to these, the hours that I threw myself into literature’s healing arms were the happiest hours for me.

- There has always been activism in jails. Did you never think or talk about this?

Activism in the face of the usurpation of democratic rights has got to be one of a person’s natural rights. But, in jail, preserving one’s health is also exceptionally important to enable one to keep up one’s activism. Staying inside and resisting is also a form of activism. So, I did not think of engaging in activism. I never spoke to my friends about this, either.

Message to those on the inside: Stick in there – we’ve reached the end

- What is your advice to those who are on the inside or will be?

Let me reply to this question with a quote from a master, Nazım Hikmet. “I mean, it’s not that you can’t pass ten or fifteen years inside and more - you can, as long as the jewel on the left side of your chest doesn’t lose its lustre.” Let this reference to Nazım Hikmet’s poem from which I quoted an extract and a recommendation to read it also serve as a reply to this question. The poem “Some Advice to Those Who Will Serve Time in Prison”. For, the advice of a master who served many long years in jail retains its validity nowadays.

- Your colleagues Akın Atalay, Murat Sabuncu, Kadri Gürsel, Ahmet Şık and Emre İper are still in prison. Perhaps you have a word for them.

Dear Akın Atalay, Dear Murat Sabuncu, Dear Kadri Gürsel, Dear Ahmet Şık and Dear Emre İper, “Stick in there – we’ve reached the end.”

En Çok Okunan Haberler

-

Rus basını yazdı: Esad ailesini Rusya'da neler bekliyor?

Rus basını yazdı: Esad ailesini Rusya'da neler bekliyor?

-

Yeni Ortadoğu projesi eşbaşkanı

Yeni Ortadoğu projesi eşbaşkanı

-

Esad'a ikinci darbe

Esad'a ikinci darbe

-

İmamoğlu'ndan Erdoğan'a sert çıkış!

İmamoğlu'ndan Erdoğan'a sert çıkış!

-

WhatsApp, Instagram ve Facebook'ta erişim sorunu!

WhatsApp, Instagram ve Facebook'ta erişim sorunu!

-

‘Yumurtacı müdire’ soruşturması

‘Yumurtacı müdire’ soruşturması

-

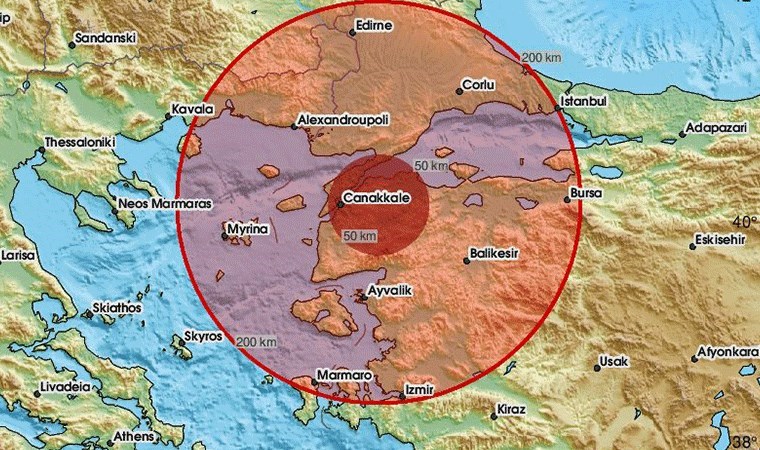

Çanakkale'de korkutan deprem!

Çanakkale'de korkutan deprem!

-

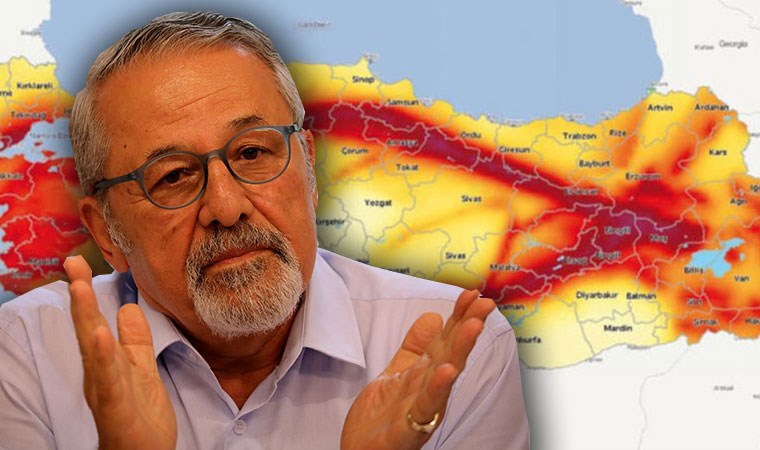

Naci Görür'den korkutan uyarı

Naci Görür'den korkutan uyarı

-

6 asker şehit olmuştu

6 asker şehit olmuştu

-

Kurum, şişeyi elinin tersiyle fırlattı

Kurum, şişeyi elinin tersiyle fırlattı